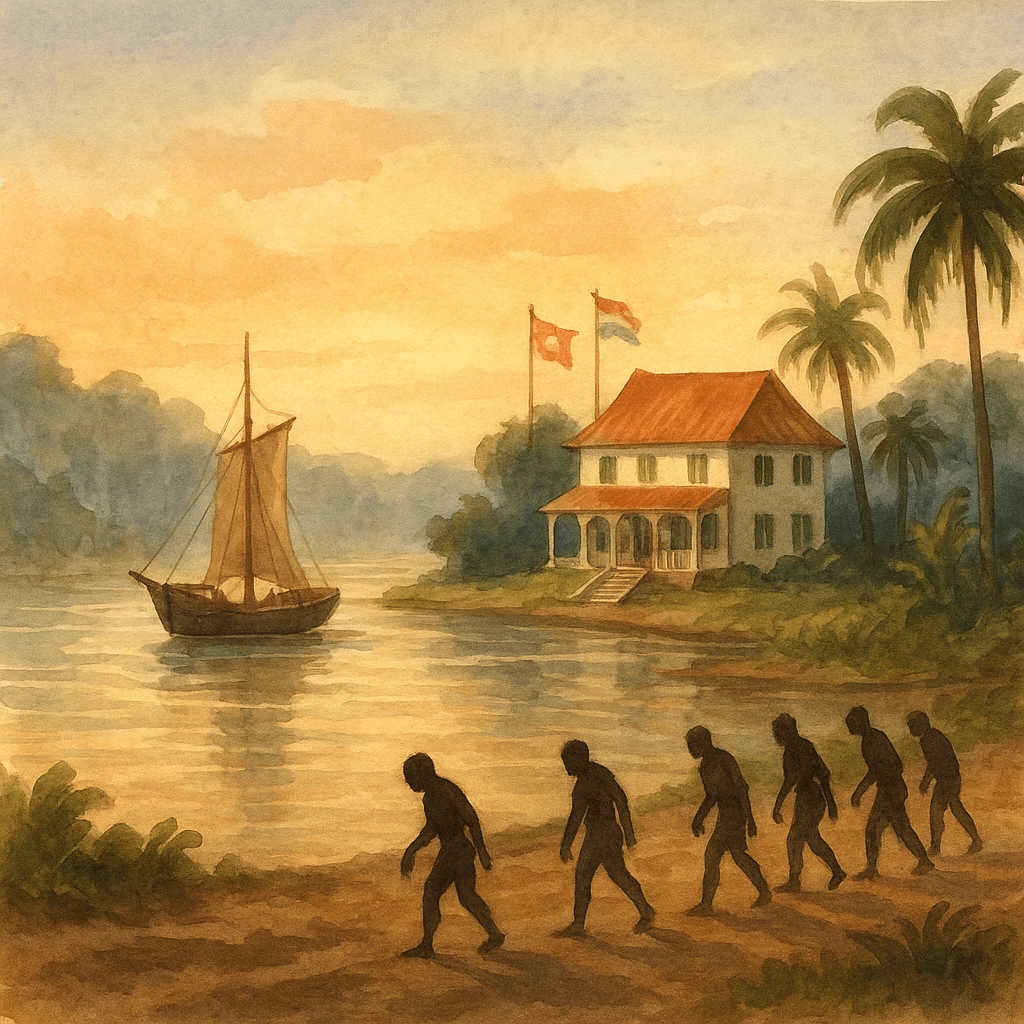

Imagine dense rainforest meets European flags on the riverbank. In the 17th century, the Dutch, English, and French swept into Suriname, eyeing its fertile land. They set up sugar, coffee, and cocoa plantations along the Suriname River, fundamentally reshaping the land—and its people.

1. The Transatlantic Slave Trade Arrives

To work these plantations, colonizers brought enslaved Africans by force. More than 250,000 endured the Middle Passage; most never stepped foot back in Africa. Those who survived faced brutal, exploitative conditions—tremendous labor under unbearable oversight.

2. Resistance, Flight, and the Rise of the Maroons

But Surinamese resisted, fiercely. Many enslaved people escaped into the rainforest to form Maroon societies, including the Ndyuka, Saramaka, and Matawai. They fought guerrilla wars with the colonizers, negotiated peace treaties (as early as 1760!), and secured self-governance deep in the forest. Their culture remains strong today.

3. Changing Tides: Abolition and Emancipation

The path to freedom was long. The Netherlands abolished slavery in 1863—but full emancipation didn’t come until 1873. That decade saw bonded labor systems like “Staatstoezicht,” where formerly enslaved folks worked under contracts that barely differed from before. True freedom was still a hard-won prize.

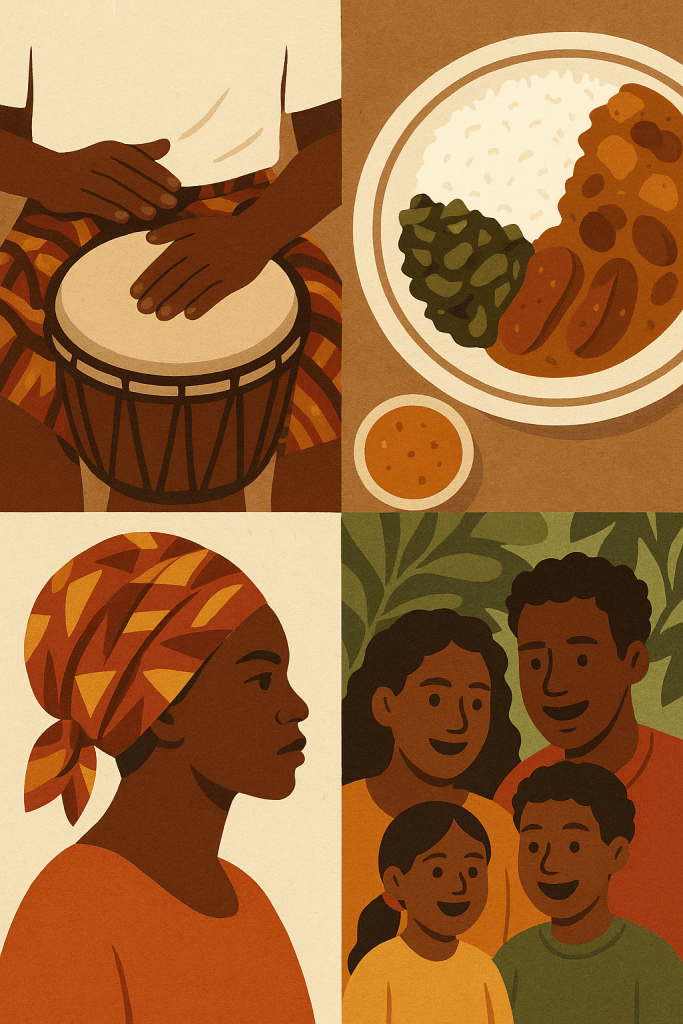

4. Cultural and Social Legacy

Slavery and colonization didn’t just shape the past—they continue to shape how Surinamese people see themselves, celebrate, speak, and connect. The echoes of that era live on not as chains, but as roots anchoring modern Suriname in resilience and cultural richness.

4.1 Language as Resistance and Resilience

During slavery, enslaved Africans were forbidden from speaking their native languages. Out of this oppression, they forged new ways to communicate—resulting in Sranan Tongo, a creole language mixing English, Dutch, Portuguese, Spanish, and African influences. Today, it’s more than just words—it’s a proud symbol of survival and creativity.

4.2 Spirituality and Storytelling

Religious practices blended African spiritual beliefs with Christianity, creating unique Afro-Surinamese traditions like Winti—a spiritual system that honors ancestral spirits and the natural world. Passed down orally, these beliefs were a form of resistance, preserving identity when written culture was denied.

4.3 Maroon Autonomy and Legacy

The Maroon communities—descendants of escaped enslaved Africans—still live in the interior, maintaining distinct customs, governance, and ceremonial life. They continue to pass down traditional crafts, music, herbal knowledge, and oral history, anchoring Suriname in a heritage of independence and pride.

4.4 Music, Food, and Fashion

You hear the legacy in kawina drums and aleisi chants; you taste it in dishes like pom, herheri, and peanut soup, rooted in African culinary survival skills. Even Surinamese fashion—like the boldly patterned angisa headscarves—tells stories: during colonial times, women folded them in code to express emotion, rebellion, or messages without saying a word.

4.5 Social Structures and Identity

Colonial policies tried to separate and rank people by origin—enslaved, indentured, free—but Surinamers forged new bonds across boundaries. Today, that’s part of the national identity: multi-ethnic, multi-faith, and proud of it. Afro-Surinamese and Maroon communities remain central to movements for social justice, equality, and cultural recognition.

Why This Matters…

*Bonus

Modern Suriname’s multicultural richness and layered identities are direct outcomes of colonial history. Knowing the roots of language, customs, and community makes today’s diversity more meaningful. It helps us move forward with understanding, not erasure.